Commissioning in Schools

The fourth grade classrooms are too warm. A motor is broken. The vice principal's office is stuffy. A louver is stuck. What happens when problems like this crop up in most school districts? How do they impact the building's energy use? How does it detract from the quality of the teaching and learning? Can most school districts even begin to answer these questions?

By Kelly M. Kirkland, CSBA, O'Brien & Company

At the Central Kitsap School District, the core team of facilities professionals know exactly what is going on in each school, and how it impacts utility costs district-wide. The ongoing commissioning they undertake improves the indoor environment for both students and teachers, and saves the district hundreds of thousands of dollars each year.

Definition of Commissioning: Commissioning is a systematic process of ensuring that a building is working as it is designed, in accordance with the owner's needs, and at peak efficiency.

Commissioning: Facilities manager as Detective

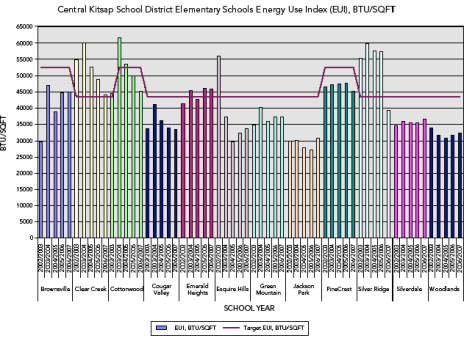

It may not be as full of drama as CSI, but it's every bit as meticulous. Each month, Central Kitsap School District's crack team of facilities professionals review their utility data for clues to wasted energy, and investigate the problem schools to find the culprit. The commissioning process started with simple metrics. By comparing the Energy Use Index (EUI), which is kBTUs per square foot, against schools across the Puget Sound region and within the District, Central Kitsap identified which of their schools were the biggest energy users.

Richard Best, Director of Capital Projects and Facilities, says, "our maintenance staff understand individual components of their buildings well, but not how the whole system works together." To get the help he needed, he hired an outside firm to help the district in their first attempt at commissioning. "We found enough good information on the first four projects and, in anticipation of additional mechanical/electrical capital projects, we decided that we should hire someone in-house."

Funded in part by Puget Sound Energy's Resource Conservation Manager (RCM) program, Central Kitsap hired an in-house commissioning agent and Facilities Project Manager, George Kevins. George is a mechanical engineer who works hand-in-hand with Becky Asencio, Environmental Resource Coordinator. Kevins worked as a private commissioning agent before moving over to the school district. Asencio, a chemical engineer by training, handles indoor air quality issues, energy tracking, asbestos issues, and materials safety data sheets. "They are a great match" Best says. "George looks to make sure we're getting the best energy savings, and Becky keeps an eye out for the comfort of the students and staff." Asencio manages a database to log the energy data, and creates graphs and charts to bring to their meetings. Best meets with his team monthly so that they can compare current trends to recent history. "When we see energy use beginning to creep up we go back out and take a look. That's why measurement is so important. Given that the degree days were the same, why are we burning more energy? Was it a special event or something that needs to be fixed?" explains Best. (Degree days are a measurement used to determine heating and cooling needs.) The team compares each school against other schools and since the last time it was commissioned.

Their monthly meeting, looking for minor variations, is just part of the picture. They also take an in-depth look at the top three or four worst-performing schools from the previous year. Armed with utility bills, and a full inventory of the types of systems in the building, age and history of the equipment, Kevins and the mechanic assigned to those buildings inspect every piece of equipment and take note of what they find. Is it operating? Is it operating as it was intended? If not, why not?

Control Issues

Besides a dedicated staff, the best thing Central Kitsap has going for them is a robust Direct Digital Control (DDC) program that not only turns equipment on-and-off, but allows staff to view the precise conditions in multiple spots in each school in nearly real-time (within 24 hours). "This data is much more useful than an electric and gas bill every month or two," laughs Best. The DDC doesn't record energy use, but Central Kitsap gets data from their utility, Puget Sound Energy. Best says, "We're a member of their EUI [energy use index] program so we can print out exactly what we use each day by going online. I use that to look at how much we're burning in the middle of the night. We should be using roughly half a Watt per square foot."

Modern DDC systems are a network of equipment controls and sensors, with a software program that talks to and coordinates them all from a central location. When the 4th grade classroom at PineCrest Elementary gets too warm, the DDC can open a louver to increase ventilation. Most schools have some kind of central building control system, but the newer DDCs are superior in that they provide an exceptional level of detail to the building operator. Central Kitsap can see the floor plan for every school in the district, and click on individually-controlled pods to see what's happening with each piece of equipment in that area. "When we look back at the data one day at a time, we can tell what time the kids were in class versus when they were in between classes in the hallways," says Kevins. Sensors can send back information on the temperature, carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, relative humidity, and VOCs (volatile organic compounds). "We usually don't care what the exact CO2 level is at any given moment, it's more helpful for us to look at trends." Sometimes, the exact data is critically important. Kevins adds, "if the temperature in the central district server room gets too high I get an urgent email from the DDC which means I don't get a frantic call from our IT staff."

While Best's team looks at the big picture, the mechanics assigned to each school can access the DDC from any computer in the district, set their building to run on whatever schedule is needed, and receive at their discretion email alerts about anything the DDC monitors.

Results

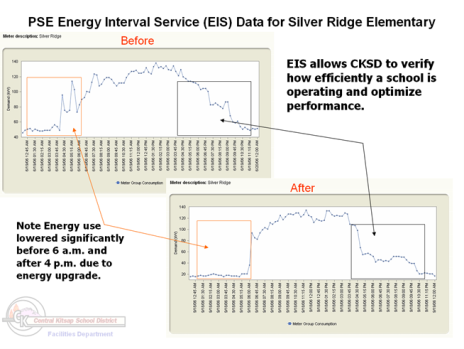

In 2005, Central Kitsap took a closer look at Silver Ridge Elementary. The 50,000 square foot building, constructed in 1990, was using much more energy than the District's other elementary schools, so in 2005 it was targeted for an energy improvement project and retro-commissioning. Silver Ridge utilizes electric heat pumps for heating. The DDC control system for heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) elements was upgraded to allow more control of the heating schedules and locations, as well as better damper controls. The HVAC system and its DDC system were fully commissioned. The combination of the upgrade and commissioning resulted in a 32% reduction in energy use and avoided costs of $22,000 in the first year. The following year, in spite of a colder than normal winter, the school had a 20% reduction in energy as compared to the base year, with additional avoided costs of $6,000.

Since 2001, Central Kitsap has received over $800,000 in grants and rebates for energy efficiency improvements mostly from Puget Sound Energy. Typically awarded for a specific project, they've received money to upgrade everything from programmable thermostats to a new lighting system for the stadium. They figure that the 30 hours they spend annually in planning meetings compared to the $150,000-$200,000 they save each year is a pretty good return on investment.

The school district used the above chart to compare individual schools' performance over time, to the target EUI, and to other schools that should have similar energy use. They identified poor performers and commissioned those buildings. Click here for a larger graph.

Central Kitsap's Top Tips For starting a Commissioning Process

1. Start somewhere. If you don't have good historical energy data for some places, start by measuring your Energy Use Index (EUI) and comparing it to schools, both in and out of the district.

2. Make time for it. If you don't have dedicated staff to manage the process, look into getting a Resource Conservation Manager. These positions are often partially funded by utilities.

3. You can't manage what you can't measure. Set up a system that allows you to monitor energy use data on an ongoing basis. If you have the resources, and have a DDC system work with a vendor who will set up floor plan graphics that precisely match your buildings so you really know what you're looking at.

4. Make a plan. Put together an energy program for each building that takes into account the age of the building, its history, and the type and age of its systems. This will help guide your commissioning process and provide a way to track your findings.

5. Get the right help. If you don't have someone one staff who is qualified to do commissioning- and it is a highly skilled profession-consider hiring someone to do it for you.

6. Document everything. Documentation will help you track exactly what you have, where it's located, what it's supposed to do, when it was tested and the results, what needs to be fixed and what needs to be monitored.

7. Listen. Your commissioning agent or DDC system won't tell you the whole story. Listen to the building staff and students to make sure the building is working for them. A successful commissioning process should save energy and reduce indoor environmental quality complaints.

8. Look for incentives. Contact your local utilities to see what kind of programs are available to help schools with energy upgrades. Many grants are available for specific projects, especially if you can demonstrate that you've done your homework and can show how much energy you'll save.

9. Punch that list. Your documentation will help you fix problems as you find them or delegate tasks across the maintenance department.

10. Be vigilant. At some point you may have trouble reducing your energy use dramatically any further. Congratulations! But unless you continue to monitor there is nothing stopping waste from creeping back.

Additional Resources

- Building Commissioning Association

- EPA web site on Commissioning

- Oregon Green Schools Program

- O'Brien & Company

- Puget Sound Energy's Resource Conservation Manager Program

- Washington Green Schools Program

Kelly M. Kirkland, CSBA is a Project Associate at O'Brien & Company, a sustainability and green building consulting firm that works with educational facilities to achieve certification under the LEED rating system and the Washington Sustainable Schools Protocol. The firm has been instrumental in bringing sustainability improvements to schools from design and construction to operations and maintenance. Kelly can be reached at kelly@obrienandco.com.